Introduction

A seismometer is equipment that measures and records ground motions. It operates on the same principle as a damped inertial mass oscillator.

Within the scope of this documentation, the operation of seismometers will be limited to the vertical seismometer.

Principe

A seismometer is a relative displacement sensor, used to measure the movements of its support fixed to the ground. The following diagram represents the vertical linear sensor.

The seismometer consists of the following elements:

- the inertial mass \(m\) suspended from a spring of negligible mass;

- the spring with a stiffness constant \(k\), a free length spring \(l_0\), an equilibrium length \(l\), and a length in motion \(l+z\);

- a viscous damping system with a constant \(\beta\);

- the ground displacement is denoted \(z_{ground}\) and the associated acceleration \(a_{ground}=\ddot{z}_{ground}\).

Equation of Motion for the Free Damped Oscillator

By applying the fundamental principle of dynamics to the mass \(m\), we obtain the following relationship: \[\sum \vec{F} = m\vec{a}\]

The balance of forces acting on the mass is as follows (due to the seismometer’s design, the forces are vertical, so we project them directly onto the \(z\)-axis):

- The weight: \(mg\), where \(m\) represents the suspended mass in \(\text{kg}\);

- The damping force (force proportional and opposite to the velocity): \(\beta\dot{z}\), with \(\beta\) being the viscous coefficient in \(\text{N}\cdot\text{m}^{-1}\cdot\text{s}\);

- The spring tension (Hooke’s Law): \(-k(l+z-l_0)\), with \(l_0\) being the spring extension without applied force in \(\text{m}\) and \(k\) the spring stiffness in \(\text{N}/\text{m}\).

We place ourselves in a reference frame linked to the ground. The mass acceleration is therefore composed of two terms:

- \(m\ddot{z}\) corresponds to the acceleration of the mass relative to the frame;

- \(m\ddot{z}_{\text{ground}}\) corresponds to the acceleration of the frame relative to the ground.

Consequently, the fundamental principle of dynamics is written as:

\[m\left(\ddot{z}+\ddot{z}_{ground}\right) = mg - \beta\dot{z} - k\left(l+z-l_0\right)\] However, at equilibrium, we have:

\[z=z_{ground}=\dot{z}=\ddot{z}=\ddot{z}_{ground}=0\] Which gives:

\[mg = k\left(l-l_0\right)\]After simplification, the equation becomes:

\[\ddot{z} + \frac{\beta}{m}\dot{z}+\frac{k}{m}z=-\ddot{z}_{ground}\]

- Natural Angular Frequency: \(\omega_m=\sqrt{\frac{k}{m}}\);

- Damping Coefficient: \(\zeta=\frac{\beta}{2m\omega_m}\)

The equation therefore becomes:

\[\ddot{z} + 2\zeta\omega_m\dot{z}+\omega_m^2z=-\ddot{z}_{ground}\]

By setting \(a_{ground}(t) = \ddot{z}_{ground}(t)\), the equation simplifies to:

\[\ddot{z} + 2\zeta\omega_m\dot{z}+\omega_m^2z=-a_{ground}\]

Study of the Equation in Harmonic Regime

As a function of the ground acceleration

The study of the seismometer’s frequency behavior is performed in the frequency domain via the Laplace operator \(p\). The equation therefore becomes:

\[ \begin{aligned} A_{ground}(p) & = - p^2 Z(p) - 2\zeta\omega_m p Z(p) - \omega_m^2Z(p) \\ & = - Z(p)\left(p^2 + 2\zeta\omega_m p + \omega_m^2\right) \end{aligned} \]

With \(A_{\text{ground}}(p) = p^2Z_{\text{ground}}(p)\) and \(Z(p)\) being the respective Laplace transforms of \(a_{\text{ground}}(t)\) and \(z(t)\).

The transfer function \(H(p)\) of the seismometer is the ratio between \(A_{\text{ground}}(p)\) and \(Z(p)\). This transfer function is the seismometer’s response related to the ground acceleration.

\[ H(p) = \frac{Z(p)}{A_{ground}(p)} = -\frac{1}{p^2 + 2\zeta\omega_m p + \omega_m^2} \]

Its equivalent in the Fourier domain is the following:

\[ H(\omega) = \frac{Z(\omega)}{A_{ground}(\omega)} = -\frac{1}{-\omega^2 + 2\zeta\omega_m j\omega + \omega_m^2}\]

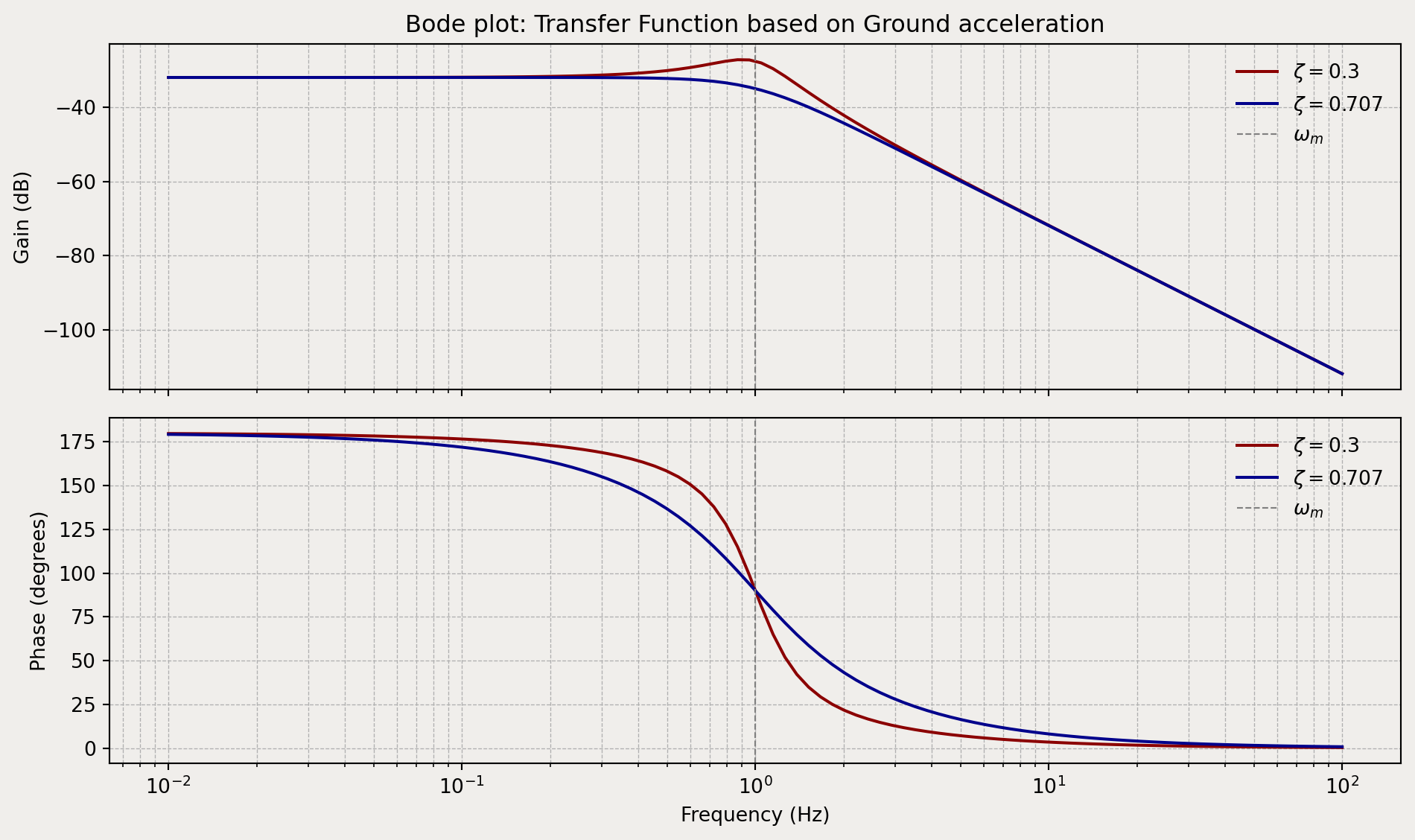

Analysis of the Transfer Function’s Gain and Phase

An asymptotic study of the equation yields the following behavior:

- If \(\omega \ll \omega_m\), then \(H(\omega)\) simplifies to \(-\frac{1}{\omega_m^2}\). The movement of the mass is proportional to the ground acceleration.

- If \(\omega \gg \omega_m\), then \(H(\omega)\) simplifies to \(\frac{1}{\omega^2}\). The movement of the sensor mass follows the ground displacement in phase opposition.

The gain (magnitude) of this transfer function is the following, using the notation \(\omega\):

\[ Gain(\omega) = \left \vert H(\omega) \right \vert = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\left(\omega_m^2 - \omega^2\right)^2 + 4\zeta^2\omega_m^2\omega^2}} \]

The phase (argument) of this transfer function is the following, using the notation \(\omega\):

\[ \begin{aligned} Phase(\omega) & = arg(H(\omega)) = arg(1) - arg(-\omega^2 + 2\zeta\omega_m j\omega + \omega_m^2) \\ & = - arg(-\omega^2 + 2\zeta\omega_m j\omega + \omega_m^2) \\ & = - atan2\left(2\zeta\omega_m \omega, \omega_m^2 -\omega^2\right) \end{aligned} \]

The transfer function is a second-order system; it therefore possesses a resonance frequency \(\omega_r\) whose characteristics are:

- it is the angular frequency at which the system’s response reaches a maximum in forced regime,

- it is influenced by damping and is therefore different from the natural angular frequency if the system is damped (\(\zeta \neq 0\)),* for a second-order system with damping (\(\zeta > 0\)), it is given by:

\[ \omega_r = \omega_m\sqrt{1-2\zeta^2} \]

- Resonance therefore only occurs if the damping ratio is less than \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \approx 0.707\).

Example plots of the gain and phase for a natural angular frequency \(\omega_m=1\text{Hz}\) and for two damping ratios \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\) and \(0.3\):

Remarks

The damping coefficient \(\beta\) is chosen so as to achieve an optimal damping ratio \(\zeta\) according to the following criteria:

- Absence of resonance \(\zeta \ge \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\), thereby reducing the risk of reaching the seismometer’s stops (or limits/bumpers).

- Maximized operating bandwidth.

These two criteria therefore impose \(\beta = \frac{2m\omega_m}{\sqrt{2}}\)

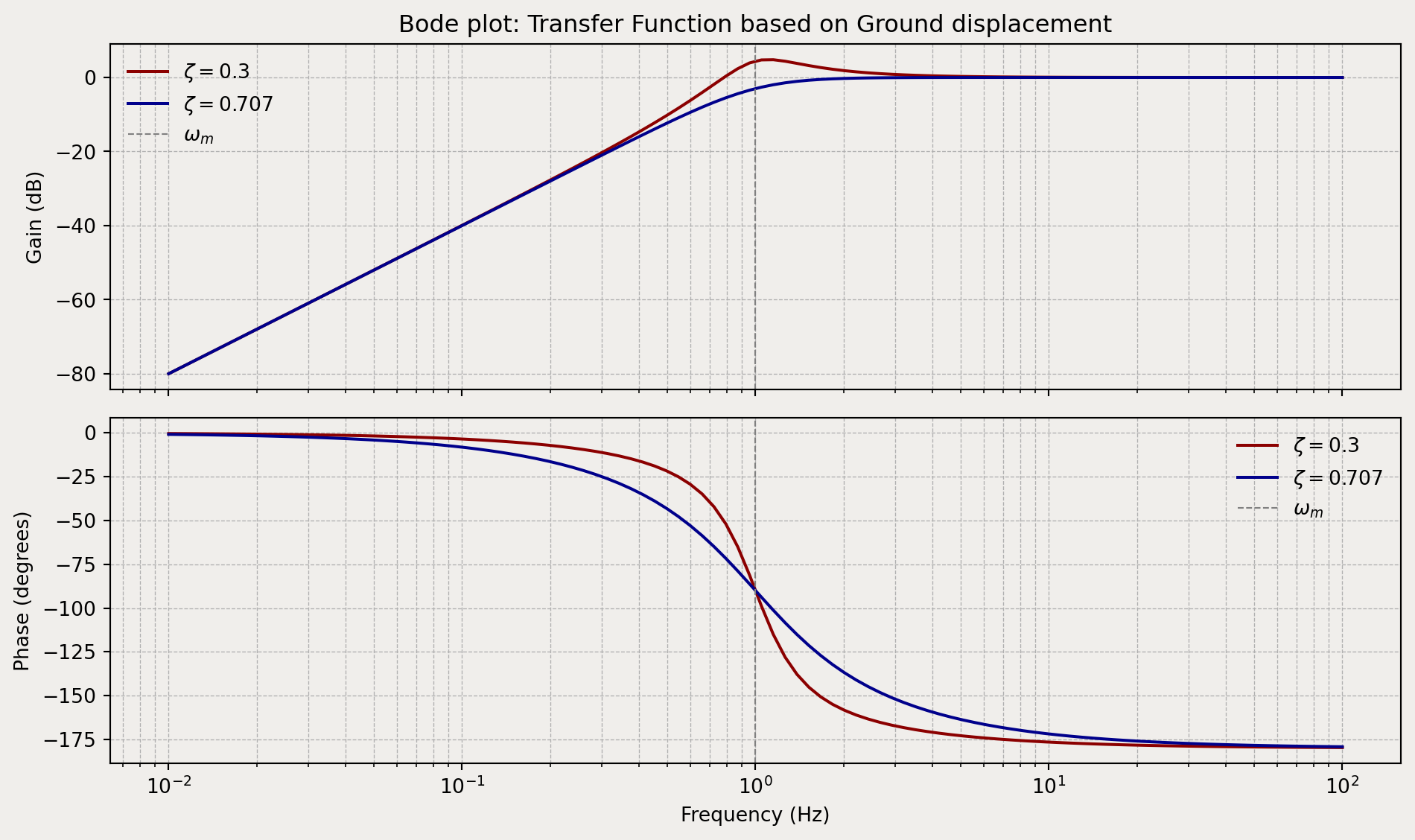

Depending on the Ground Displacement

It is also possible to study the sensor’s response as a function of the ground displacement by using the relationship between acceleration and displacement, \(A_{\text{ground}}(p) = p^2Z_{\text{ground}}(p)\).

\[H(p) = \frac{Z(p)}{p^2Z_{ground}(p)} = -\frac{1}{p^2 + 2\zeta\omega_m p + \omega_m^2}\]

\[H_{\text{displacement}}(p) = \frac{Z(p)}{Z_{ground}(p)} = -\frac{p^2}{p^2 + 2\zeta\omega_m p + \omega_m^2}\]

Example plots for the \(H_{\text{displacement}}(p)\) gain and phase for a natural angular frequency \(\omega_m=1\text{Hz}\) and for two damping ratios \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\) and \(0.3\):

Consequence of the Seismometer Equation

Limitation of the Linear Sensor

The natural period of the sensor is given by the following relationship:

\[T_m = 2\pi\sqrt{\frac{m}{k}}\]

Furthermore, at equilibrium, we have:

\[mg = k\left(l-l_0\right)\]

By introducing the equilibrium relationship into the natural period relationship, we obtain:

\[T_m = 2\pi\sqrt{\frac{l-l_0}{g}}\]

The attainment of a period \(T_m=10\text{s}\) therefore requires an extension at equilibrium of \(l_{\text{eq}}-l_0=24.8\text{m}\), which makes the realization of this type of suspension impossible for periods of this magnitude.

Therefore, to achieve periods of this magnitude, suspensions based on the LaCoste pendulum will be used.